Apologies to readers for the previous format of this page – I know, the layout wasn’t exactly the best so an improvement has been made. You will find a newspaper article on this story in this post and my analysis in the next post.

Kateri Tekakwitha, New Native American Saint, Stirs Mixed Emotions

Religion News Service | By Renee K. Gadoua Posted: 10/18/2012 7:46 am

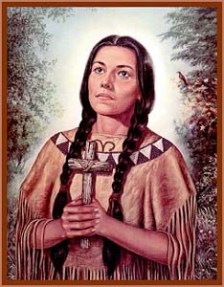

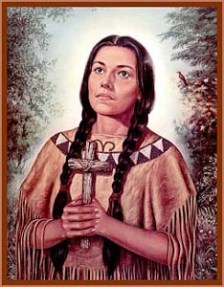

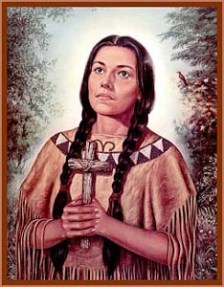

Kateri Tekakwitha

(AP Photo/ Mike Groll)

EDT Updated: 10/18/2012

SYRACUSE, N.Y. (RNS) Sister Kateri Mitchell was born and raised on the St. Regis Mohawk Reservation along the St. Lawrence River. She grew up hearing stories about Kateri Tekakwitha, the 17th-century Mohawk woman who will be declared a saint in the Roman Catholic Church on Sunday (Oct. 21).

She has long admired Tekakwitha for her steadfast faith and her ability to bridge Native American spirituality with Catholic traditions. In 1961, Mitchell joined the Sisters of St. Anne, and since 1998 she has served as executive director of the Tekakwitha Conference in Great Falls, Mont., a group that has spread Tekakwitha’s story and prayed for her canonization since 1939.

“We’ve been waiting a long time for this,” she said of the canonization at the Vatican. “It’s a great validation.”

Doug George-Kanentiio, also a Mohawk from St. Regis, was brought up Catholic, even serving as an altar boy. But he left the church at 14 when he began to practice Native American longhouse traditions.

“I had a lot of anger at the church at the things they had done to the Native people and the world and the moral compromises they made,” he said.

Yet he, too, will travel to Rome for the canonization.

“It took me a while to begin to adopt a different approach to this, not one based on history, but compassion for a young woman who was determined she was going to emulate the suffering of Jesus Christ,” George-Kanentiio said. “That passion is remarkable.”

Then there’s Alicia Cook, who grew up on the Onondaga Nation, married a Mohawk and now lives at St. Regis, also known as Akwesasne. She has always practiced longhouse religion and has no interest in Tekakwitha’s story.

“The church has been telling us for years we’re heathens,” Cook said. “The white man has hurt us enough. They intruded on our land here.”

Those viewpoints reflect the diverse, seemingly contradictory reactions to the young Mohawk woman who converted to Catholicism more than 300 years ago.

Some see it as a story of commitment and strength and an affirmation of Native Americans’ place in the Catholic Church. Others view it as the result of the excesses and arrogance of colonialism, the suppression of Native American tradition and culture, and the remnants of a missionary tradition that forced its narrow understanding of faith on others.

Tekakwitha was born in 1656 to a Mohawk father and an Algonquin/Christian mother in a Mohawk village in what is now Auriesville, N.Y. When she was 4, her parents and a younger brother died in a smallpox epidemic. The illness left her scarred and nearly blind.

She was baptized by a Jesuit missionary in 1676. Some Mohawks tormented her for her conversion, but she committed herself to Christianity and a life of virginity, practicing extreme acts of religious devotion, including self-flagellation. She fled to a Mohawk/Catholic village in what is now Montreal, and died there in 1680 at age 24.

Calls for her recognition as a saint date to her death, and the official church campaign began in 1931. According to the Vatican, prayers to Tekakwitha for her intercession were responsible for the inexplicable cure of a 6-year-old Native American boy in 2006 in Washington state who developed a flesh-eating virus after an injury.

The church typically requires verification of two miracles for sainthood. But in 1980, Pope John Paul II waived the requirement for Tekakwitha’s first miracle, citing the difficulty of confirming details of incidents said to have occurred hundreds of years ago.

Tekakwitha is the first Native American named a Catholic saint.

She was born during a time of independent Indian nations interacting with the Dutch and French, said Allan Greer, a McGill University professor who studies early Canada and colonial North America and the author of “Mohawk Saint: Catherine Tekakwitha and the Jesuits.”

“It’s a time of tremendous turmoil, with epidemic diseases, warfare, new technologies being available through trade with Europeans,” Greer said. “It’s kind of a holocaust of the Native Americans by infections from the Old World, and millions die.”

In 1667, the Iroquois Confederacy — including the Mohawks — made peace with the French and Canada; as a condition, the Mohawks had to accept Jesuit missionaries in their villages.

Central New York’s history is closely tied to the Jesuits. Missionary Simon Le Moyne, namesake of the Catholic college, first visited the area on August 17, 1655 — the year before Tekakwitha was born. From 1656 to 1658, seven Jesuits lived at the Sainte Marie mission near Onondaga Lake, fleeing after learning the Iroquois planned to kill them.

The Jesuits never hid their goal of converting souls, Greer said. And while contemporary readers may see racism and arrogance in the accounts, the Jesuits were genuinely trying to understand Iroquois culture, he said.

Tekakwitha was not coerced or victimized by the Jesuits, he said.

“She is an active and aggressive cross-cultural explorer,” Greer said. “She is in a way trying to capture their secrets. She was on a mission to get access to what empowers Europeans in a spiritual sense.”

Mitchell reads the Jesuit accounts in their historic context, and credits the Jesuits with promoting Tekakwitha’s story: “The Jesuits were able to document and report it. We had no one to document it and tell the story.”

Cook, meanwhile, is teaching her children and grandchildren Native traditions and encouraging them to learn to speak Mohawk. But she has no hostility toward Native Americans who practice Catholicism or revere Tekakwitha.

“I wouldn’t expect others to have my beliefs,” she said. “We all have our own teachings. I have my own basket to carry.”

(Renee K. Gadoua writes for The Post-Standard in Syracuse, N.Y.)

*Article courtesy of the Huffington Post.